The Late Late Toy Show generated so much excitement last Friday that you couldn’t miss it. It has become a cultural phenomenon. For many it marks the official start to Christmas. These days, with the rise of streaming services, shared TV experiences are rare. The Toy Show is one exception but it has not entered the digital age untouched. Live-tweeting the Toy Show has become a national sport. Grinches, doting families, and public relations teams are on stand by – thumbs at the ready. The children, their stories, and their innocence reach into our hearts. Even those of us who start the night full of cynicism feel a little warmer by the end.

That day, another story dominated my Twitter timeline – a record high in homelessness. On the very day that we awaited the fanfare of the Toy Show, 3,480 children were in emergency accommodation. Including adults, there are 11,400 people in such need. If they were all housed in a brand-new town, it would be among the 40 largest towns in Ireland. The term emergency accommodation seems a misnomer at this point. Emergency accommodation brings to mind American disaster movies – sports-halls filled with sleeping bags. A tornado rips through a town, the people take shelter, things are rebuilt and life returns to normal. An emergency is defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as a serious, unexpected, and often dangerous situation requiring immediate action.

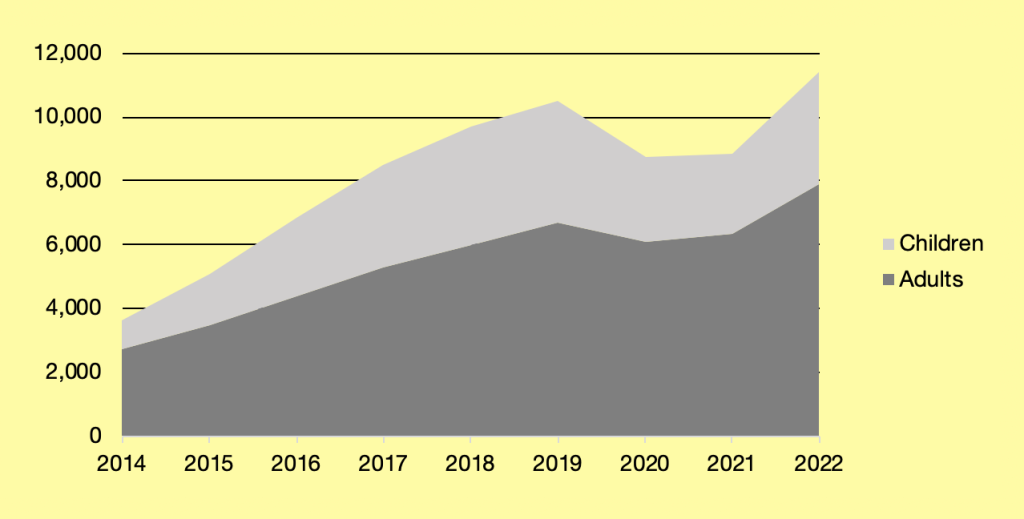

Does Figure 1 look like an emergency? Ireland’s homelessness crisis did not come out of nowhere. In reality, the shortage of housing is much worse than this chart portrays. Were it not for friends and family, many others who cannot find a home would further increase pressure on services. The numbers would be higher still if not for those who make harrowing sacrifices in order to scrape together crippling rents for substandard homes.

There are many factors driving the crisis but only some that we can readily influence. Demand is booming. Ireland’s population is the third fastest growing in the EU. In fact, Ireland’s population is growing 10 times faster than the EU average. This shows no sign of reversing. Even using the CSO’s most conservative projection, the population is expected to increase by 600,000 by 2050. This growth is due more births than deaths and inward migration. This is something to be celebrated. People are living longer and, as I wrote before, Ireland’s vibrant economy is attracting people from all over the world. Short of some cataclysmic economic or social event, it is hard to see demand for housing fall.

This leaves supply – we need to build more homes. The good news is that we’ve done this before. In 1911, Dublin had the worst living conditions of any city in the UK. Once great Georgian houses became filthy, dilapidated, tenements. In the formerly fashionable Henrietta Street, 835 people lived in just 15 such houses.* People died as their homes collapsed around them. Many more succumbed to disease. The scale of the problem was truly enormous. I often wonder how much this contributed to the desire to overthrow the political establishment. It was convenient that those to blame were “over there”. Once independence was secured, it was up to us to solve our own problems. An ambitious social housing programme was undertaken by a country of small means. Between 1930 and 1955, over 110,000 social houses were built.† This accounted for more than half the total number of houses built in the State in those years.

The neighbourhoods of Cabra, Crumlin, and Kimmage all emerged from this initiative. The developments faced opposition and they were far from perfect. Much of the infrastructure needed to sustain vibrant communities was lacking. Fintan O’Toole – raised in Crumlin – gives a brilliant, and humorous, account of those challenges in We Don’t Know Ourselves. But despite the challenges I believe these developments were overwhelmingly successful. How much bleaker might O’Toole’s account have been if those neighbourhoods were never built? If the slums were never cleared? It is easy to use the socioeconomic challenges faced by those communities as an excuse to not build social housing at such scale again. As John le Carré said “if there is one eternal truth of politics, it is that there are always a dozen good reasons for doing nothing.” There is one all important reason to do something, though – to provide people with that most basic of needs: shelter – a place to call home.

More supply alone isn’t sufficient but it is a necessary part of the solution. Without doubt, we should ensure that new developments are high quality with good transport connections, utilities, green space, permeability, etc. But when a growing number of people have no homes at all, perfection may well be the enemy of the good. We need to build housing at scale and at pace. Children shouldn’t grow up in emergency accommodation. I am sure that most people believe that and are pained by the situation but feel helpless. I think most people have broadly the same set of values but that those values may be in a different order for each individual. Everyone wants to end homelessness but not everyone can agree on the price that has to be paid – the sacrifice that must be made. That sacrifice may mean higher taxes, it may mean new construction in already settled areas, it may mean whole new neighbourhoods are built.

This is why the problem needs to be reframed. Let’s not ask “what price are you willing to pay to end homelessness?”. Instead, let’s ask “what price are we currently paying for not ending homelessness?”. With every objection, every delay, every market failure, and every unspent euro in housing budgets, we are weakening the fabric of society. Children’s hopes are diminished, migrants are victimised, and sky-high rents reduce consumption and investment. As a society we must pull together to solve homelessness because if we don’t it will tear us apart.

CN